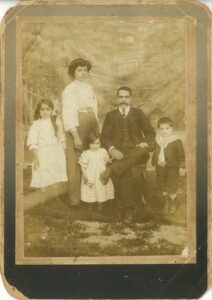

Arlene Voski Avakian was born in 1939 to an Iranian Armenian father and a Turkish Armenian mother who was a survivor of the Armenian genocide. She grew up in Washington Heights, New York, in a 5-room apartment that sometimes housed as many as 15 people. When her family moved from her vibrant neighborhood to homogenous, suburban New Jersey in 1954, she became rebellious as a survival strategy: “If I didn’t have anger, I don’t know where I’d be.”

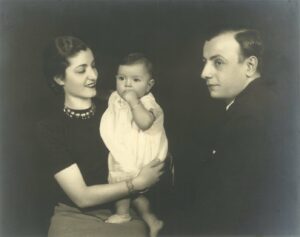

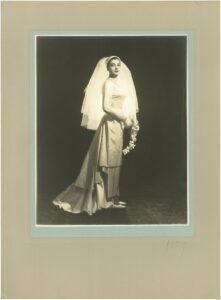

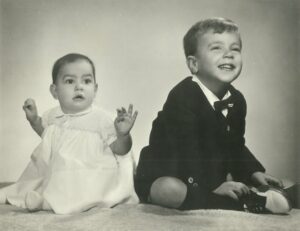

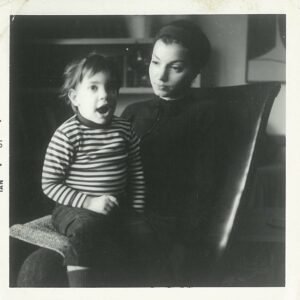

As marriage was the only way she could think of to get away from her family, Arlene married young. At age 21, she and her husband had their first child, Neal, and later a daughter named Leah. Neal was on the autism spectrum, but there wasn’t much language for it at the time, let alone support. Arlene was fiercely protective of Neal, and wouldn’t let her husband institutionalize him. Struggling to get her son’s needs met was an early political education for her, which grew into a lifetime of battling injustice.

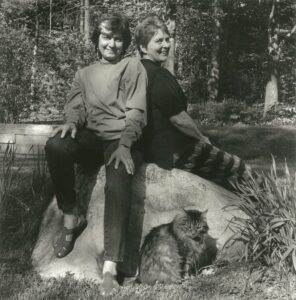

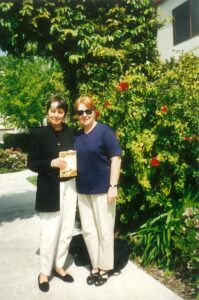

At age 24, Arlene discovered a small women’s movement in Ithaca, where she was teaching at Cornell. Feminism was exhilarating, and she started taking Taekwondo classes and wearing pants. When a friend told her she needed to move away from her undermining husband, Arlene applied to a masters program at UMass Amherst in the History department, got a teaching assistant position at UMass, and moved to Amherst as a single mother. She found a therapist for her son, through whom she also met a woman named Martha Ayres. After a year of “hanging out,” Martha and Arlene became partners, and were together for 42 years.

At UMass, Arlene completed her MA in History in 1975. As part of the Women’s Studies subcommittee, she considered it part of her job to connect with African American Studies faculty, two of whom became her academic mentors: John Bracey and Johnnetta Cole. When she decided to get her EdD at UMass, they both advised her to write a memoir as her dissertation, which became Lion Woman’s Legacy (1992). When Arlene became the Women’s Studies department chair, she aspired to establish a majority women of color department – “not just people who represented groups of color, but whose research was on women of color.” In this, she was successful.

The lesbian community in the Amherst/Northampton area was strict, with rules like not being friends with straight women. Arlene and Martha forged their own community instead, lesbian and straight women alike. When Arlene’s children both died in 2008 – Leah from leukemia, Neal from a car accident – their community showed “enormous support” to Arlene and Martha.

Shortly after her children died, Arlene received an invitation to present a paper in Turkey at the Hrant Dink Memorial Workshop on Gender and Ethnicity in the Former Ottoman Lands. The experience of being with Armenian and Turkish people was profound, and she went back to Turkey nine times in ten years. After those ten years, Martha got cancer and passed away. “I was able to take really good care of her without one bit of resentment,” Arlene says of that time. “I’d get tired, all of that, but the love was just so strong.”

Today, Arlene feels “settled” in her identity as an Armenian and a descendant of genocide survivors. She exhorts white people to learn their history, and advises future generations to “look for your strengths” in a world that would make them a victim.