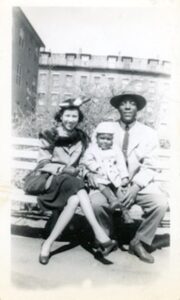

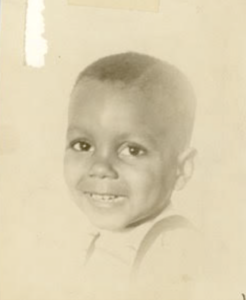

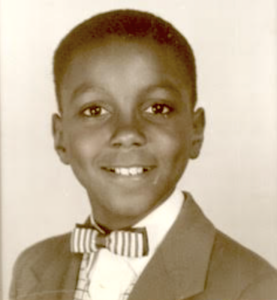

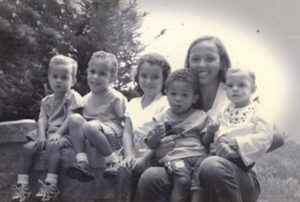

David Wilson was born in 1944 in Boston, to Black parents who worked as domestics for White families around the perimeter of Boston. They would dress up like they were going to another job and bring their work clothes with them when they left the house; David didn’t find out what they did until he was a teenager. For the first 15 years of his life, David lived in mostly-White public housing outside of Boston. Then his family moved to a three-decker in Boston, where his mother encouraged him to meet a nice Black girl at church and get married. That girl was Sandy, and they ultimately had three kids together. David recalls, “I was on a path towards, ‘Get married, have kids, get a good job, raise your family and don’t rock any boats.’”

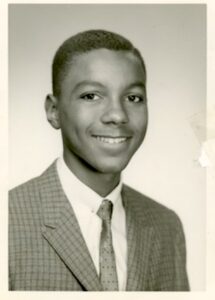

After graduating from Northeastern University, David entered a two-year management training program at New England Telephone (later Verizon), leading to a 30-year career at the company. For the first time, David noticed the differences between himself and his White counterparts, and all the “unwritten rules” of the workplace that no one had ever told him.

Fifteen years into his marriage, David acknowledged that he was questioning his sexuality, and sought out counseling. After a year, he told Sandy that he was gay. Her immediate response was, “What can we do to work together, to continue raising our family?” Sandy and David sat down with their three kids to deliver the news and answer all their questions, and the whole family was supportive.

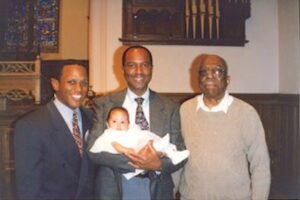

Coming out to his parents in the midst of the AIDS crisis was not so simple: in the first 20 minutes of their conversation, David’s mother said, “You’re going to die.” But within two years, he had his parents’ approval of his new partner, Ron. Five years into dating, Ron and David moved in together. But even after opening up to his family, David’s attitude at work remained the same: “Keep your head down,” don’t make waves, don’t come out.

Then one day in 1994, David came home to find Ron laying across a bag of leaves in the driveway, not moving. At the hospital, the staff told David to take a seat; they “saw no relationship between me and him.” Three hours later, David finally found out that Ron had been dead on arrival.

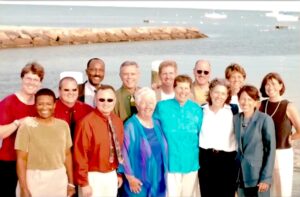

After Ron’s funeral, David allowed himself to be angry in a way he hadn’t felt before. He came out at work and started advocating for other gay and lesbian employees. He went to a grief support group, which led him to Rob Compton. Rob and David fell in love, and held a commitment ceremony in 2001. Days later, GLAAD approached the couple: did they want to be among the plaintiffs in a lawsuit to legalize gay marriage in Massachusetts? Rob and David said yes.

Goodridge v. Mass. Department of Public Health attained victory in 2003, and Rob and David were married the first day that gay marriage was legal in the United States: May 17, 2004, the 50th anniversary of Brown vs. The Board of Education. When the pastor pronounced them married, the entire church erupted in cheers. From “keeping his head down” to sticking his neck out, David had come full circle.