Wakefield was born on September 12, 1952 in Chicago, Illinois. Both his parents served as role models of strong civic leadership — his father was president of the local library association, and his mother was an election judge and PTA president. Taking his parents’ lessons of altruism to heart, Wakefield pursued teaching. While he was passionate about serving his students, he was unsupported by school administration as the only African American teacher. When administrators criticized him for creating an interracial cast for the school production of Peter Pan, it was the last straw. He went on to work in Sears management, where leadership refused to promote him alongside his white colleagues even though he was equally qualified.

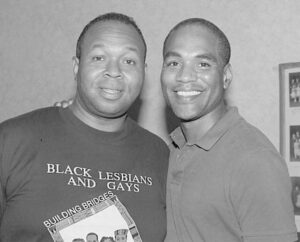

Wakefield also started spending nights out at local gay bars and began a series of long-term relationships. In a later relationship, he adopted three children, and brought his partner and children to his uncle’s home one Thanksgiving. Wakefield’s uncle pulled him aside and told him that his “friend” and children were not welcome. Leaving the party, Wakefield finally told his father that he was gay and his “friend” was his partner. Over the years, Wakefield and his father grew to accept one another. At one New Year’s party, his father proudly showed off a newspaper with the headline, “What gay activist, Steve Wakefield, says about HIV.” But since Wakefield’s father was also named Steve Wakefield, he asked Wakefield to just go by his last name, because he didn’t want to be mistaken for a gay activist. Wakefield obliged.

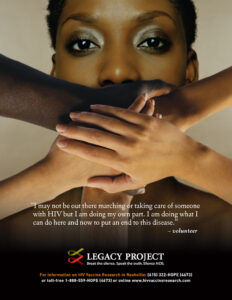

Meanwhile, Wakefield began volunteering at at an underground storefront clinic providing Hepatitis B services to gay men, the Howard Brown Health Center. He soon joined the clinic board, and at age 34, he became a full-time deputy to help transition the clinic into HIV care. Wakefield spent his days working on HIV epidemic response with doctors and his nights caring for and grieving loved ones, including his partner. By 1987, Wakefield was exhausted at Howard Brown. He then became director of the Test Positive Aware Network for five years, sponsoring support groups for people and families affected by HIV. Ultimately, processing so much grief in so little time became overwhelming, and he resigned.

Wakefield then started working with The Night Ministry, supporting homeless youth. At the end of his first week on the job, he remarked to a friend, “It was great. Nobody died.” On his own time, he showed up at the NIH’s scientific meetings, advocating for community representation in NIH committees. He co-published HIV treatment protocols and watched new research unfold firsthand. Five years later, he realized his heart was still in HIV work. He took time off to travel and conduct community surveys in South Africa. Then in January 2000, he moved to Seattle to work with Dr. Karry Corey’s team on community engagement with HIV vaccine research. After 20 years, he made the difficult decision to retire.

In his interview, Wakefield reflects on how much of the COVID-19 response was built off the existing research from HIV/AIDS. He also discusses the importance of listening for effective community engagement, the racism he’s experienced despite being a prominent community leader, and his undying determination to meet the needs of those around him.